Map

This stretch of the Thames from London Bridge to the Albert Docks is to other watersides of river ports what a virgin forest would be to a garden. It is a thing grown up, not made. It recalls a jungle by the confused, varied, and impenetrable aspect of the buildings that line the shore, not according to a planned purpose, but as if sprung up by accident from scattered seeds. (Joseph Conrad, The Mirror of the Sea)

I arrived at the docklands early Sunday morning, stepping off the Jubilee line at Canary Wharf tube station. The train was disappointingly busy. Where I’d quite self-consciously gone looking for an almost sinister emptiness the train was actually relatively full. Mainly with people who looked like they were going sailing.

Canary Wharf tube station is a self-consciously bombastic, the proclamations of its own importance (a half-cut city trader on a late night booty call) echoing noisily across its cavernous interior. At one end a bank of escalators tower out of the gloom, their destination bathed in sunlight. Like an irritating acquaintance at a costume party the escalators demand you acknowledge what they look like – the the stairway to heaven in A Matter of Life and Death, the gleaming tasteful edifices of Gattaca, something from that movie that you can’t quite place.

Like everything in this particular part of the docklands they feel unreal, borrowed from fiction. As you walk past 6ft high electronic billboards screen displaying CNN, the DLR glides overhead on thick, smooth rails, crunching into the station like a state-of-the-art rollercoaster. From the centre of canary Wharf you gaze out at a cinematic landscape, an anonymous near future all-too-familiar for anyone with a childhood as wasted on over-hyped movies as mine was.

In one of his books (I can't remember which) Douglas Coupland explains away the ridiculous number of mediocre action films made in Vancouver as being a consequence of its anonymous familiarity – its generically imposing skyscrapers and its cultured lawns and its city monuments that could be anywhere important. Signifiers of the flashy urbanity of New York, Los Angeles, Shanghai, Kuala Lumpur, Metropolis. The Docklands however seems to come at film from entirely the opposite angle. As it scrambles breathlessly into existence it seems desperate to quote cinema, rather than be quoted by it. It stitches itself into the shape of a finely tailored business district from an infinite patchwork of Hollywood films made between about 1985 and 2002.

It speaks of its own importance through the language of big budget multiplex cinema – a language its prospective inhabitants implicitly understand. And thus it constructs itself as a singularly modern image of aspiration. This is where you could work, this is where you could live, this is what you could become, like something from the movies.

When I was growing up, the sortof-town next to our tiny village was just about big enough to have its own miniature business park. Every time we drove into Cambridge we would pass one office that seemed to be made entirely of a glistening, sky blue glass. I was always transfixed. Imagine, I thought to myself, imagine working in a place like that; imagine staring out through a window of tinted glass at the world around you – that’s the life. As impressed as I was by a miserable-looking two story office in a meek little business park just north of Cambridge, I can barely imagine what I would have thought, at the age of about five, of the Docklands. It would have struck me with all the wonder of Disney’s tomorrowland; a freshly moulded simulacrum of what Hollywood told us the future would look like.

But of course, at that point I couldn’t have visited the Docklands. Not in the sense that it exists today. It was at that time a half-started building site. Once the biggest docks in the world. Then eight square miles of wasteland for around twenty years. Then, in complete contrast to the organic jungle described by Joseph Conrad, it was resurrected; carefully planned and consciously remade by a government-funded Quango. Born around 1980, the new docklands is only as old those people they are desperately trying to populate it with, aspiring city-workers in their late twenties. Like them it is rising fast, relaxing its still slightly awkward frame into expensive new habits. But like them it is barely even half-completed.

To my quiet delight, once you strike out a few streets away from Canary Wharf you are quickly engulfed by building sites and cranes, tarpaulin flapping eerily on an otherwise empty street – a different kind of movie. The docklands are still endearingly tatty round the edges, their naked, fevered ambition showing through the cracks. Black and white photos of imagined dockside complexes are plastered up in front of looming skeletal frames. I found myself walking through a shopping centre-like complex consisting entirely of estate agents, all of them decked out in dynamic, tastefully complementing primary colours – like a series of Microsoft Powerpoint templates. All of them offering for sale grown-up looking pencil drawings of expensive apartments. Ready to be snapped up by aspiring young graduates from Liverpool, Leeds, Sussex, small villages north of Cambridge; buying unbuilt houses with the six figure salaries they’re soon to be earning.

There’s something incredibly endearing for me about the docklands. As well as feeling like a 1000 films I sat and watched with my parents on a Sunday evening with a gluttonous plate of roast dinner piled on a tray in front of me, it reminds me of how I felt then. Of the reassuring vision of my elderly parents slowly coasting down a row of houses in the car, an address gripped in my mum’s hand – no, surely it couldn’t be this one, goodness – the admiring beams on their faces as I lounge in the doorway of my make-believe hollywoodised superhome. My parents who grew up in council houses or in their grandparent's terrace house in Croydon. It reminds me of the stinging ambition that used drive me to the point of distraction. That still does if I’m honest though converted by a force of will from the glossy apartments of the docklands to the nominally more worthy accolades of academia and theatre. But I still remember wandering round the motorshow at the NEC, dreaming of the car I would use to go and visit my parents.

Blueprint for a Show

Get a little way from the centre of the docklands and it still has the feel of an edgeland, as if you’ve stumbled into a half-finished makeover, revealing something authentic and endearing disappearing fast under a sea of simulated sophistication.

I found that on a Sunday morning you could wonder along empty quaysides, only seeing maybe a distant figure on the opposite side of the water. I like this. I also like that the awkwardly placed bridges make it impossible to get to that person with any great haste.

Perhaps you could create something a little like Small Metal Objects, taking advantage of the discontinuity between the great distance and the intimacy of a spoken voice. But more desolate. Not in a crowd. Perhaps you and another are connected by telephone. But with hands free headsets (a gadget that still gives me that same frisson of grown-up futuristic excitement that I once got from a cheap glass office block).

Across an empty wharf littered with building works and static cranes, you can see a figure. In your ear you can hear their fevered talking. They are looking for something.

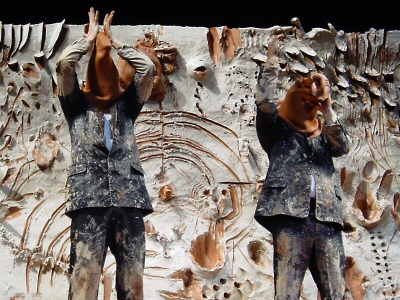

They are a representation of everything around them. A product of bad Hollywood films. A little like Mel Wilson’s wonderful solo show Simple Girl, they are attempting to live out a borrowed ideal and are failing. But rather than longing for wistful European romance, this is the universe of the mediocre Hollywood action thriller. Demolition Man keeps springing to mind, I don’t know why. Die Hard and its imposing LA skyscraper. Yippee ki-ay motherfucker. The character's language is a patchwork of Americanisms (not even… Hollywoodisms). There is a frenzied ambition to this pulpy dream and like the docklands itself it is pretty tatty and half-formed round the edges.

What were those films always about? Saving a city from bombs or terrorists. Appropriately docklands has its own rather messy history of that. Perhaps this character, a young over-eager city boy of some kind, believes himself to be the only one able to solve an imminent threat. And here he is rushing around full of bluster and slightly hopeless Hollywood bombast, the trappings of his young success quickly sacrificed at the alter of this increasingly obsessive action plot.

Of course if it was a direct telephone link between you and this person, you’d be able to talk back. The audience member would have to be implicated in this world somehow. Maybe they see you as the cowardly side-kick, or the evil mastermind, or a love interest. Perhaps we could have all three – some kind of conference call, with three audience members co-opted into this story played out on the enormous movie set that is the docklands. In some way all three are needed to validate this absurd narrative, and their failure to live up to their roles makes this fiction increasingly fractured.

I’d like it if it ended in a very public place, with a very public scene. Lots of shouting. And in which the audience could implicate themselves – in front of the unknowing general public – with some big cinematic display fitting of their ‘character’, or from which they could quietly back away, leaving our hopelessly protagonist all the more ridiculous, a tragic broken figure lost in his own fantasy.